But isn’t superstition still rampant among us?

Most superstitions are rooted in fears of the unknown and attendant efforts, however futile, to exert control over one’s own destiny. Superstition and cultural misunderstandings pervade Benjamin Christensen’s 1922 Danish silent film Häxan: Witchcraft Through the Ages_—the inspiration for this exhibition—and although the production was made in the early 20th century, artists are still grappling with the shadowy ambiguity of the unknown today. The works included in Häxan Daze_ whisper of the past and hint at the disquietude of change: Dawn Roe’s investigations of a faraway place haunted by previous uses of its land; Benjamin Gardner’s installations of paintings and found objects inspired by folklore and mystic texts; Bob Jones’s transformations of discarded items into moments of wonder; and Bill Conger’s meditations on the very nature of existence.

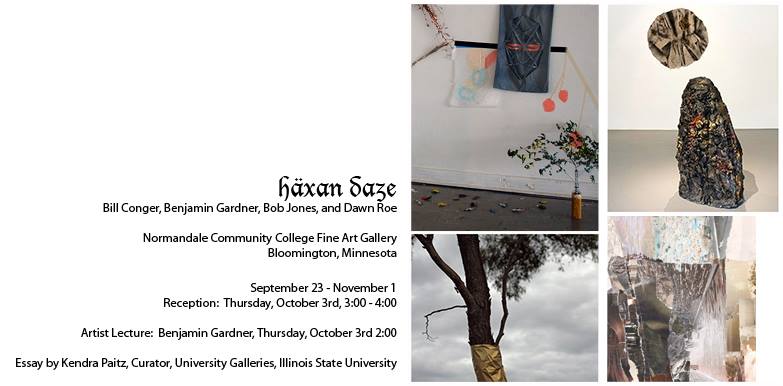

With chiaroscuro lighting, twisting branches, wafts of smoke, and occasional “golden” punctuations, Dawn Roe’s Goldfield Studies (2011-2012) beckon viewers into a mysterious setting. Years of reading fairytales and Gothic novels attune one’s senses to the secrets that may be concealed by the endless trees and layers of dank matter. The Australian bushland featured in the artist’s work has transitioned from a natural location to one in which its ground’s precious elements were stripped away by gold miners, leaving the terrain perforated by countless abandoned mine shafts. Roe “understand[s] this space as a repository of cultural memory constructed from the opposing perspectives of indigenous and colonial settler narratives, pastoral landscape representations, folklore and myth.”¹ Quietly intervening in the landscape, she draws attention to its history by placing gold fabric and paper around trees and in streams. She documents the results in elegantly recorded photographic diptychs and triptychs and a three-channel HD video. Her multiple viewpoints emphasize the impossibility of capturing the conflicted land’s “physical and psychic traces.”²

Bob Jones’s survey (2011)—a raw, round canvas segmented by dark lines made of oil—resonates with the division of land and stripping of resources pertinent to Roe’s work. Known for intuitively transforming everyday materials, Jones is often referred to as an alchemist. His the magician (2009) toys with this notion but, in keeping with much of his other work, can be read as both playful and ominous. The black “figure” made of oil and tar is crowned with spiraling, spray-painted cardboard triangles that seem to function as a beacon of light. The three-sided shape is tripled, reinforcing the artist’s use of a form and number sacred to occultists, Freemasons, and ancient Egyptians alike. Jones’s totem (2007) likewise employs three forms: slightly squashed semi-spheres made from sawdust and black paint that evoke both a trail marker and an apocalyptic snowman.

For his recent installations, Benjamin Gardner combines ephemeral natural elements—particularly plants, leaves, and sunlight—with paintings, drawings, and sculptures. His weary song (2013)—an installation comprised of an abstract geometrical drawing cut into a soft gray pillowcase, constellations of tape applied directly to the walls and floor, and flora collected in the surrounding area each time the piece is exhibited—unites the constructed spaces of his home and the gallery with the greater natural world encompassing them. Drawing visual inspiration from hex signs and mandalas, the artist transforms his base materials into visual incantations that resonate with the histories of each component. The slowly shifting light in Gardner’s sun wreath (2013) marks the transition of each passing day; the bisected circular shape cut from black fabric is hung in a west-facing window. As the late afternoon sun begins to relinquish its powers to the twilight hours, its dying light pours through the negative space forming a fleeting “drawing” of a wreath on the gallery floor. In accordance with the beliefs of both ancient sun-worshippers and Christians awaiting Judgment day, bodies in many cemeteries—which are often memorialized with wreaths as symbols of eternal life—are oriented east/west rather than north/south to follow the path of the sun.³

One can also look to primitive notions to interpret Bill Conger’s The Drop (2013), a (thus-far) impeccably preserved carcass of a wasp. Although a contemporary audience may fear the insect for its vicious sting, in ancient times, wasps were considered as “augurs of evil,” prophets for the weather, and foreshadowers of the future direction of relationships.4 Just as one may focus on the striations, coloring, and geometry in the artist’s fractured collages of media imagery, he finds their apt counterpart in the wasp’s perfectly folded and veined brown-black wings and striped legs. Devoid of pins, labels, or diagrams, this tiny corpse does not function as a specimen, but rather as a confrontation with the inevitability of death. When paired with the downward descent implied by its title, perhaps the wasp functions as a harbinger for the seemingly inscrutable future.

—Kendra Paitz is Curator of Exhibitions at University Galleries of Illinois State University, where she has had the honor of working with each of the artists in this exhibition. Häxan Daze (on view September 23 – November 1, 2013 at Normandale Community College Fine Art Gallery, Bloomington, Minnesota) was curated by Kristoffer Holmgren, Gallery Director at Normandale Community College.

———————————————————

The title of this essay quotes a title card in Benjamin Christensen’s 1922 Danish silent film Häxan: Witchcraft Through the Ages.

¹Dawn Roe’s artist statement, 2012.

²Ibid.

³Puckle, Bertram S. Funeral Customs: Their Origin and Development. London: T. Werner Laurie Ltd., 1926.

4⁴Morley, Margaret W. Wasps and Their Ways. New York: Dodd, Mead, and Company, 1900.